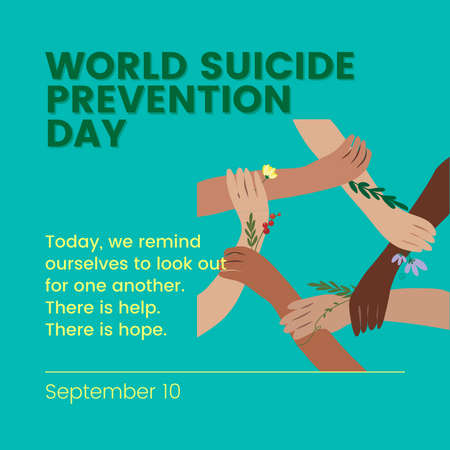

The month of September is celebrated globally as Suicide Prevention and Awareness Month. To learn more about suicide and how we can support each-other, see this article. If you need to talk to someone or if you are in need of urgent help, please proceed to the nearest hospital emergency room, or proceed to the end of this article for the contact numbers of various local 24/7 crisis lines.

Stereotypes aside, as an organization providing psychological care, We Thrive’s work admittedly has a lot to do with conversations. It is something we take for granted, not always realizing that this very peculiar human capacity is one of the building blocks of human civilization (Crystal et al., 2023). Conversations are also one of the building blocks of human life: as psychologist Lucy Foulkes puts it, when conversations “allow us to learn something important about ourselves, about the other person, or about the world” (Foulkes, 2021), truly remarkable things happen. Such conversations, when they are “meaningful”, can turn even otherwise mundane chatter (what we label “small talk”) into subtle gateways for deeper interactions (Macquire, 2023). They make possible the flourishing of all those aspects of being human: sensing and holding our emotions (Lieberman et al., 2007), articulating the various aspects of the self (McLean and Morrison-Cohen, 2013), developing new behaviors and perspectives (Albright et al., 2016), relieving and easing painful experiences (Kardas, Kumar, and Epley, 2021), making sense of life as a whole (Tarbi et al., 2021), and much more. Speech of this kind has a literal healing effect, hence the well-earned stereotypical predominance of “talk therapy” methods in clinical psychological practice (Lindberg, 2023). As social beings, as author Arthur Dobrin puts it: “With conversation, we find a place where we belong” (Dobrin, 2011).

In our ongoing observance of Suicide Prevention and Awareness Month, we want to offer some practical points for reflection for having meaningful conversations, particularly those you want to check in on and support through difficult experiences.

The look and feel of a meaningful conversation

The main feature of a meaningful conversation is the experience of being “heard” — an experience which is, without exaggeration, “one of the most basic, yet potent needs we have as social beings” (Fowler, 2022). Most of us know from personal experience how painful not being heard can be, and how influential it can affect our own ability to hear others. Not being heard can have many precipitating factors: maybe there are basic differences in communication style (Khiron Clinic, 2021); or maybe the capacities of one or both people in the conversation to hold big or uncomfortable feelings are limited (Brosch, 2015). It could be some other factor, like adverse childhood experiences (Zlate, 2020), which are not within our present control. Whatever the case, when we are not heard, some of our most fundamental needs — the needs to feel that “we are taken seriously, that our ideas and feelings are acknowledged, and that we have something to share” (Nichols, 1995) — cannot be met.

So how do we get to meaningful conversations where we feel taken seriously, acknowledged, and feel that what we share has value? We may be tempted to offer advice right away or resort to offering affirmation.

But “problem-solving” is not the same as “hearing”, and our impulse to give instructions or shoo away difficult feelings with aspirations of pleasantness, while usually very well-intentioned, may not reflect the other person’s true needs. This is what is often meant by “toxic positivity”: when the resolution to be quote-unquote “happy” is not grounded in the present reality which might demand more emotional complexity.

So having said that, what does “hearing” actually look like? Thankfully, a few scholars have looked into this. In a series of studies, the concept of being “heard” — described by the authors succinctly as “a key variable of our time”, given our modern propensities for distractions — was operationalized according to five components (Roos, Postmes, and Koudenburg, 2021). Here, we will present how these were understood and some points for reflection to guide how we apply these to making our conversations truly meaningful.

- Recognizing our “voice”. This is about “being able to express myself freely, that is, being able to say what I want to say.” In meaningful conversations, there must be that sense that, while some social filters might be appropriate in any given situation, we are able to say what we think or feel without fear of being criticized, demeaned, or thought poorly of. It is the sense that, right or wrong aside, what we say is welcomed.

Reflection: In our conversations, do we offer a sense of security that allows the other person to say what they need to say, and that we are willing and able to welcome what they say — even if they’re about something difficult and uncertain?

- Receiving “attention”. This is about feeling that the other person “focused their attention on what I said”. In meaningful conversations, there is a conscious effort to home in on the details, verbal or otherwise. It is the sense that what we say merits curiosity, and that there is a richness in what is being said that is worth patiently drawing out.

Reflection: In our conversations, do we offer expressions of interest that communicate to the other person that what they have to say is important, and that we really want to understand them?

- Receiving “empathy”. This is the perception that “the other tried to take my perspective and emotionally understand me.” In meaningful conversations, the affective contents of what we say — not just the words, but the conditions that led us to say what we say — are appreciated. It is the sense that the other person is resonating with us at a level that is deeper than the dictionary definitions of our statements, and that we are allowed to speak with more vulnerability, confident that, at the minimum, our vulnerability will be cared for.

Reflection: In our conversations, does our presence invite the other person to let their guard down, even a little, so that what they say communicates more truthfully what their hearts dictate? (At least to the extent possible, given the circumstance. Emotions are complex, after all!)

- Receiving “respect”. This is the feeling that the other person “valued what I said (my voice) and me as a person”. In meaningful conversations, while all human activity is prone to human errors of misunderstanding, we are taken and honored as we are. It is the sense that whatever prejudices there may be are set aside — or at least owned up to, honestly — and that the interaction is grounded in a commitment to the fact that we are human beings deserving of compassion.

Reflection: In our conversations, does our approach show the other person that we accept and honor them as they are, however and whatever they may be?

- Experiencing “common ground”. This is the perception that we can “understand each other’s point of view”. In meaningful conversations, there is a kind of exchange that allows both people’s perspectives to be influenced in a constructive way, allowing not just greater understanding of the nuances of these differences, but a greater appreciation of how such differences can lead to the same goals of cultivating a more meaningful life. While there may be significant divergences in the way we come to our conclusions, these conclusions are ultimately grounded on a desire for the greatest good — and that our conception of the “good” can be deepened and strengthened by one-another.

Reflection: In our conversations, do we communicate an openness to hearing the other person’s views, and an openness for our own views to be positively influenced by them?

Being able to initiate and sustain such a potent human activity is one of our best means for promoting healing for ourselves and one-another. By cultivating these five components, we can be better placed to leverage the power of conversations to cultivate human flourishing both within and beyond our difficult experiences.

For mental health support services, email us at resilientteams@wethrivewellbeing.com or contact us to sign-up for sessions with our mental health clinicians.

If you need to talk to someone or if you are in need of urgent help, please proceed to the nearest hospital emergency room, or call these 24/7 crisis lines:

DOH-NCMH Hotline

0917-899-USAP (8727)

0966-351-4518

0908-639-2672

(02) 7-989-USAP (8727)

1553

Hopeline PH

0917-558-HOPE (4673)

0918-873-4673 (HOPE)

(02) 8-804-HOPE (4673)

2919

In Touch Crisis Line

0917-800-1123

0922-893-8944

(02) 8-8937603

References (in order of appearance):

- https://wethrivewellbeing.com/world-suicide-prevention-day-responding-to-suicide-with-resilience-and-compassion/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/language

- https://psyche.co/guides/how-to-have-more-meaningful-conversations

- https://carolinemaguireauthor.com/how-to-make-small-talk/

- https://www.healthline.com/health/mental-health/talk-therapy#how-effective

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17576282/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15283488.2013.776498

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5344154/

- https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp-pspa0000281.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0738399121003335

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/am-i-right/201112/conversation-makes-us-human

- https://thedmcclinic.ie/blog-the-importance-of-being-heard/

- https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/listen-up-why-you-dont-feel-heard-in-your-relationship-0810154

- https://www.pacesconnection.com/blog/adverse-childhood-experiences-and-interpersonal-relationships

- https://www.compassionate.center/docs/Why-listening-is-so-important.pdf