Qui-Gon: “Do not center on your anxieties, Obi-Wan.

Keep your concentration here and now, where it belongs.”

Obi-Wan: “But Master Yoda says I should be mindful of the future.”

Qui-Gon: “But not at the expense of the moment. Be mindful of the living Force, young Padawan.”

***

Spoiler warning: This article contains references from scenes in the Star Wars movie franchise. Reader discretion is advised as these references may be spoilers for those who have yet to watch the movies.

The Force has always been an enigmatic, mysterious concept in the Star Wars universe harnessed by both Jedi and Sith alike that fuels their abilities and lightsabers; and has been thought of as an “invisible energy” that ties every being in the universe together. In order for The Force to be harnessed, one must look insightfully into themselves to find a balance between the light and the dark parts within; to attune oneself into the present moment; and expand one’s awareness of thoughts, emotions, and sensations, allowing them to simply “just be” without judgment and letting go of them when need be.

The ways in which Star Wars’ The Force has been described and harnessed by its users can often be interpreted as a fantastical analog to the present-day concept and experience of mindfulness, a way of doing things and living life that has been practiced and used in different therapies (especially those of the Cognitive-Behavioral family of therapies such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) to help people live meaningful lives while acknowledging and tolerating suffering as an essential human condition, and accepting and enacting change within ourselves and with others.

It is a well-known fact that Star Wars hugely borrows a multitude of motifs and themes from different cultures and spiritualities. The nature of The Force and much of the Jedi way of life borrows their motifs from the spirituality of Zen Buddhism (“Zen”, for short)— not a religion or ideology, but a way of living and the manner by which a person thinks or does things mindfully. The Jedi Code, the code that guides the way of Jedi life and their morals, is closely inspired by The Four Noble Truths of Zen Buddhism. These Noble Truths were taught by The Buddha himself and dissects upon the nature of suffering, how we may transcend beyond that suffering, and how we may live meaningful lives despite suffering: The First Truth, The Reality of Suffering; The Second Truth, The Cause of Suffering; The Third Truth, The End of Suffering; and the Fourth Truth, The Eightfold Path Leads to Nirvana (or simply called “enlightenment” or “awakening”, freedom from suffering).

Zen considers suffering as a fundamental condition of humanity through The First Truth, where life is not without physical and mental suffering, and emotional stress. We simply cannot live perfect lives and run from suffering. The Second Truth teaches us that suffering is not random at all, and comes from the attachment to desires, our moving goalposts— our should haves, would haves, and shouldn’t haves— and our pursuit of and hanging on to impermanent, fleeting pleasures. In this pursuit and effort to satisfy and hold on to our desires and material wants that are essentially impermanent, these desires and material wants are destined to be lost that would in turn, lead to our disappointment, regret and pain. We see this in the example of Anakin Skywalker, who would later become the infamous Darth Vader after he is consumed with his fears. He becomes extremely attached to Padme Amidala, and encounters a vision of her dying in the future. Consumed by the future and his fear of losing her, he seeks to become more powerful by heeding his Dark Side, allowing himself to be overridden by his emotions in an effort to prevent his fears. Out of his fear of losing who it was that he was most attached to, he stopped at nothing to attempt to prevent that from happening— even if he must upturn the galaxy and harm the innocent.

***

Yoda: “Careful you must be when sensing the future, Anakin. The fear of loss is a path to the dark side.”

Anakin: “I will not let these visions come true, Master Yoda.”

Yoda: “Death is a natural part of life. Rejoice for those around you who transform into the Force… [Extreme] Attachment leads to jealousy. The shadow of greed, that is.”

Anakin: “What must I do, Master Yoda?”

Yoda: “Train yourself to let go of everything you fear to lose”

***

But if life is not without suffering, and that it is a fundamental, inevitable condition of humanity, how then, can we be freed from it? The Third Noble Truth answers this, as supported by Master Yoda’s wisdom above: by letting go. In order to alleviate the effect of suffering on our lives, we must first remember its source: attachment to impermanent desires and material wants. While it is perfectly human to desire and want, it is the tenacious chase over often-unrealistic desires and wants that we cannot fulfill as well as with the fear of losing already-attained pleasures that fills us with pain. We often mistakenly illusion ourselves that it is want and desire that holds on to us in a vice grip. We are conditioned that we must absolutely “get that job”, “own that big house”, “have a complete family”, or “make it big” in life. While these are ideal, can contribute to a meaningful life, and would be amazing to all have in our very own lives, we find that the world is never ideal. When despite our best efforts and resources we languish still chasing after these—perhaps, we can take a pause and discern with our wisdom if these goals still work for us realistically. Zen teaches us that it is we who clutch over these wants and desires— that we are indeed empowered to decide to loosen our own grip over them and ultimately let go of things that no longer work for us.

Suffice to say, mindfully “letting go” can be easier said than done. It is not something we can do overnight. It is a habit, a process, a series of learned behaviors that we must cultivate over time and train ourselves that it all becomes easier in the long run. In the same vein, we look at when Master Yoda trains a young Luke Skywalker in Dagobah. Luke, being a new Force-user, attempts to Force-pull his crashed ship out from sinking in the swamps with little yield and readily gives up. Master Yoda admonishes him, “You must unlearn what you have learned. Try not. Do, or do not. There is no try.” Thereafter, Master Yoda shows what a lifetime (in his case, over eight hundred years) of practice of The Force, a lifetime of meditation and practice of The Jedi Code cultivates this ability in incremental steps. These incremental steps of practicing mindfulness and training our minds to let go more readily, when done daily, snowballs in weeks, to months, and to years of mastery. We then see Luke in the more recent The Last Jedi movie, now a Jedi Master as was once Yoda before him, with the ability to easily muster the power of his mind and The Force exponentially more than when he was first trained in Dagobah. We often stop ourselves short on our own journeys towards changing the way we think towards wellbeing, telling ourselves punitively, “I can’t change,” or that “I’ll always be like this”. To circle back on Master Yoda’s words: “Do, or do not.” Like Luke’s journey of mastering his own mind and The Force, we must start somewhere, anywhere and decide to take the first step, keeping one foot after the other day after day in training our own minds to be more mindful.

It then becomes a question of “how” we can cultivate a habit of readily and mindfully letting go of wants and desires that no longer serve us. This is where the Fourth Noble Truth of Zen comes in: The Eightfold Path. This Eightfold Path is a fundamental teaching in Buddhism that outlines the path towards the alleviation of suffering, consisting of eight interdependent and interconnected steps that guide us toward ethical conduct, mental discipline, and wisdom, ultimately leading us to health and well-being where we strike the balance between the extremes of self-indulgence and total self-denial (hence, The Eightfold Path also dubbed “The Middle Way”). The Middle Way resonates powerfully with the canonical, alternate version to the original Jedi code (often criticized for having been written in an extremist perspective of only validating our “Light” sides) in newer Star Wars media, that establishes harmony with the Sith Code (which has also been written as an extremist perspective of only validating our “Dark” sides). In finding this synthesis with the Sith code, the existence of emotion is valued and heeded with peace, ignorance is forgiven and equipped with knowledge, passion is tempered by serenity, we find harmony with our chaos, and death or impermanence is accepted as a part of life. Hence, the balance between Light and Dark is struck, the duality of our persons and reality itself made meaningful and nuanced.

***

Emotion, yet peace.

Ignorance, yet knowledge.

Passion, yet serenity.

Chaos, yet harmony.

Death, yet the Force.

An alternate version of The Jedi Code from the comic, Star Wars: Kanan 7th issue

***

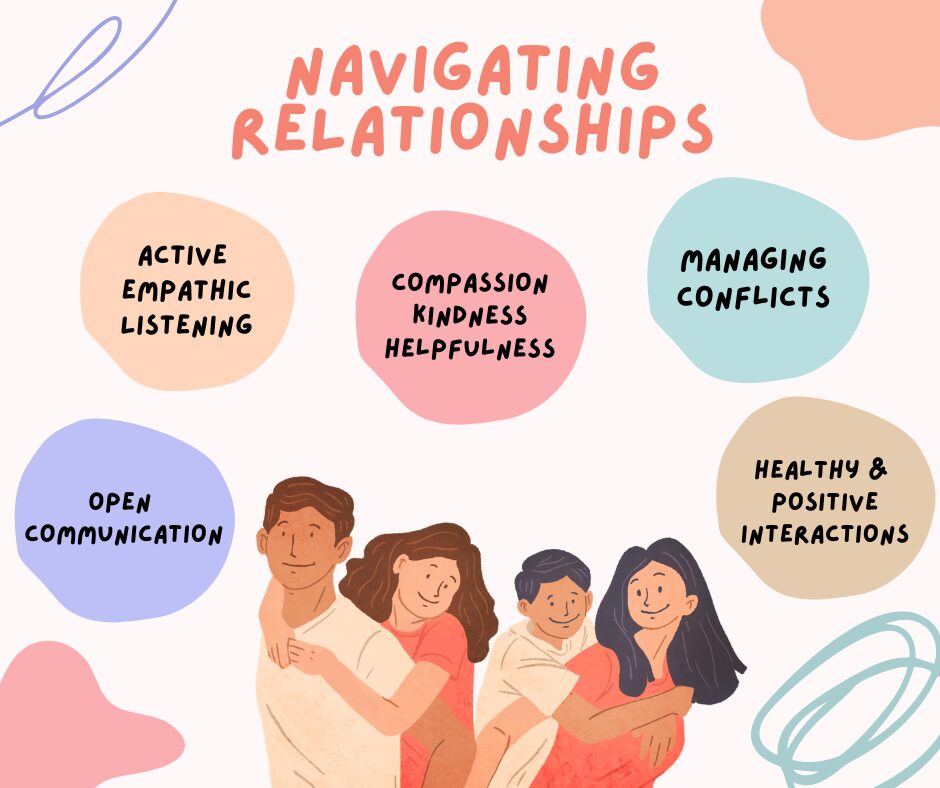

Among these steps in The Middle Way or The Eightfold Path is The Right Mindfulness in cultivating this balance over our “Light” and “Dark” sides. What is mindfulness, exactly? Mindfulness has to do with the quality of awareness or the quality of presence one brings to daily living. In her Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Skills Manual, psychologist and Zen practitioner Marsha Linehan (2014) defines mindfulness as “a set of skills, a practice of intentional observing, describing, and participating in ‘what is’ nonjudgementally, without attachment in the moment, and with effectiveness”. Mindfulness as a practice is the repeated effort of directing the mind back to awareness of the present moment; a repeated effort of letting go of judgements and letting go of attachment to current thoughts, emotions, sensations, activities, events, or life situations. To better understand mindfulness, we talk about “what” it is and “how” it is done.

On “what” mindfulness is, it is:

- Observing. It is attending to events, emotions, and behaviors without necessarily trying to put a stop to them when they’re uncomfortable or painful, or trying to prolong them when they’re pleasant. It is allowing yourself to experience and tolerate with awareness, in the moment, whatever is happening, rather than leaving a situation or trying to put an end or prolong an emotion. It also includes the ability to discern whether an event, an emotion or behavior is coming up and being able to decide to step back and let go if need be.

- Describing. It is applying verbal labels to internal and external events that we’re able to exercise effective communication with others so that they may understand us, and allows us to recognize the happenings in our internal worlds— our thoughts, emotions, and sensations— so that when they’re recognized, we are then able to decide how to treat with them.

- Participating. It is the ability to participate with our attention and being able to enter oneself completely into the goings-on and events of the current moment, without completely separating from them.

On “how” mindfulness is done, we would think about how we can mindfully observe, describe, and participate:

- Nonjudgementally. It is quite human to judge, to evaluate things and events such as emotions or thoughts as “good” or “bad”. Instead, what mindfulness encourages us to do is to take a nonevaluative approach, wherein we drop our judgements of things and events as either falling in the binary of “worthwhile” and “worthless”; and rather see things happening as simply, outcomes or consequences of behaviors and events. Because of this shift in understanding, we learn to see that when these behaviors and events cause destructiveness and suffering upon oneself and/or others, we can uphold the space to decide on changing these behaviors or events.

- One-Mindfully. This is about focusing the mind and awareness in the current moment’s activity, rather than splitting attention among several activities or between a current activity and thinking about something else in auto-pilot mode. Often, we’re distracted by thoughts and images of the past, worries about the future, relentless and punishing thoughts about our problems and our negative moods; that we forget to live in the present moment for what it is. When doing things one-mindfully, we focus our attention on one task at a time, engaging in it with alertness, awareness, and wakefulness.

- Effectively. Being mindful entails focusing on what works, rather than what is “right” versus “wrong”, or “fair” versus “unfair”. Being effective means allowing yourself to let go of the need to be or feel “right”. This determination to be “right” can in itself, be self-defeating, unrealistic, and sometimes harmful. However, we must strike a balance between validating our own perceptions, judgements, and decisions as “right” to an extreme, and giving in extremely such that we invalidate ourselves completely.

An exemplary example of mindfulness being illustrated in the Star Wars franchise is when Rey meets Luke Skywalker in The Last Jedi, coming forward under his tutelage and asking him about the true nature of The Force. She has very little idea of what harnessing The Force means, and so, he invites her to meditate and experience it for what it is. During this mindfulness exercise that he invites her to do, a meditative practice, she closes her eyes and attunes her full attention to what exists around her in the present moment— things often taken for granted when our attention is stuck thinking about the past and the future. Rey, during this meditative scene, perceives the world around her, accompanied by a visual montage that shows us that we can focus our attention to even the smallest and simplest of external things and events (such as the grass, the sunlight, the sound of the waves and creatures around her), and that doing so cultivates our ability to become mindful.

***

Luke: Sit here, legs crossed [tapping to a rock]. The force is not a power you have. It’s not about lifting rocks. It’s the energy between all things, a tension, a balance, that binds the universe together. Close your eyes. Breathe. Just breathe. Reach out with your feelings. What do you see?

Rey: The island. Life. Death and decay, that feeds new life. Warmth. Cold. Peace, and violence.

Luke: And between it all…?

Rey: …balance. Energy. A Force.

Luke: And inside you…?

Rey: Inside me, that same force.

***

When Luke invites her to look inward, Rey finds that she can also be mindful of her internal workings, an awareness of both her Light and Dark, her hopes and fears. As she sits in meditation, she’s slowly led by her mind into her dark place. The emotions of anger and fear are ushered into her consciousness as dark imagery overwhelms her. She doesn’t resist the Darkness within her, but still acknowledges it; rather than to turn a blind eye to it and deny its existence. At times, our Dark side exists and resurfaces, simply mechanisms that have protected us in the past hard-wired overtime. Like Rey, we can see our Dark sides as what they are, see them eye-to-eye, acknowledge them and discern what it is they are telling us. In the words of Master Luke, “It offered you something you needed.”

While The Force doesn’t exist in our galaxy, we can still learn from how The Jedi use it to guide their lives. We can use these lessons about the Force as a gateway to studying mindfulness and putting practices into action.

Ready to live The Jedi Way and practice mindfulness in your everyday life? Here are some mindfulness practices that you can do:

1. Mindful Immersion

In the words of Jedi master Qui-Gon Jinn, he reminds us, “Remember, concentrate on the moment. Feel, don’t think. Use your instincts.” He reminds a young Anakin before his podrace to be present in the current moment, to free his mind from distractions and overthinking.

Practice:

- Choose one activity that you do daily. It could be preparing or eating a meal, drinking your favourite beverage, listening to music, taking a walk outside or doing an exercise.

- For five minutes, use your senses— touch, taste, smell, sight, hearing— and focusing your full attention to notice the sensations around you, whether it be the temperature of your beverage, how the soles of your feet touch the ground as you walk, or the the flavor of what you’re eating.

- When you notice your mind wander to anything else that is not in the present moment, acknowledge the distraction briefly, and redirect your attention to the activity that you are doing and the sensations that come with it.

2. Gratitude Journaling

Just like Jedi Masters who equip their Padawans (or students) with the practice of The Force, there are people in our lives that have helped us and made us who we are, supporting us along the way to become better and towards living a more meaningful life. For these things and people, we learn to count them as gifts that we may have taken for granted and only realize to give thanks when we pause. Remembering the people and things we are thankful for can help our minds mindfully attune to the positive things in our life.

Practice:

- Select any blank notebook as your gratitude journal. You may also use a document on a computer, or an app on your phone.

- Either just after you wake or right before bed, write down the date and at least three things or people you are grateful to have in your life, and write a sentence (or two) about why they make you feel this way. Your gratitude can be for something big or small.

- Occasionally look back through the journal and notice how much you have been grateful for. When you can, thank the people who have played a part in what you’re grateful for!

3. Riding The Wave [Of Emotions]

In a moment of redemption in Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, Kylo Ren converses with the memory of his father, Han Solo, and voices out about his struggle to let go of his extreme anger, that which fuels his Dark Side, “I know what I have to do [to let go], but I don’t know if I have the strength to do it.” To which his memory of his father replies to him, “You do.” In the same way, when we feel extremes of emotion, we feel like we have no control over them and are gripped by them. Mindfulness enables us to acknowledge our extreme waves of emotion and allow us to ride them until they tide over, tolerating them until we return to equilibrium.

Practice:

- Whenever you think of an uncomfortable emotion, pause and notice it. Acknowledge what you are thinking (i.e. “I’m thinking that I’m not good enough”, “I’m having the thought that I might make a mistake.”) or what you’re feeling (i.e. “I don’t feel confident” or “I noticed I’m feeling anxious.)

- As you notice your feelings, observe everything about it. How does your body react to it? What are the sensations you’re feeling? Perhaps you feel tension in your jaw, or your back muscles, or that you’re breathing much more quicker. Also notice how long you’re lingering on the thought or emotion.

- Ask yourself, “What are my feelings telling me? What is it that my body needs?” Perhaps it is to re-evaluate what we are doing, or to take a break and rest, or to advocate for ourselves and our needs.

- Remind yourself that feelings are temporary and will dissipate in due time, or can be likened like a wave that gets smaller as it reaches the shore. You may remind yourself, “This feeling will pass.” while stepping back and practicing techniques that help your body reach equilibrium (see: body scan and mindful breathing below).

4. Body Scan

The Jedi practice being attuned to the sensations of their body, with their body to keep them in fighting fit form in protection of the innocent. With this attention to the state of their body and cultivating a more in-touch relationship with it, we are more able to notice the way our body reacts to certain events and emotions, and when we’ve acknowledged these, we are signaled to listen to what it is we need to care for ourselves.

Practice:

- Sit down on a chair in your most relaxed position. Take deep breaths, inhaling through your nose and exhaling through your mouth slowly to center yourself. You may close your eyes or open them— whatever is most comfortable for you.

- Starting with your left foot, scan every part of your body— each toe, each joint— with your mind. The speed at which you scan depends on how much time you have, but the slower, the better.

- As you scan, note any sensations you feel, without focusing on why you might feel them. You may also sense nothing more than your internal systems doing their thing. That’s okay.

- After you’ve scanned your body from your toes to your scalp, expand your awareness to your body as a whole. Focus on your breath, and gently open your eyes if they were closed, and bring yourself back in to the present.

5. Mindful Breathing

As Master Luke trains Rey in harnessing The Force, he instructs her to, “Breathe. Just breathe.” While breathing is an automatic thing that our body does, we forget that it is something readily accessible to us to focus our minds on, with concentration and attention that helps us build our ability to become more mindful. Mindful breathing can help us concentrate and center ourselves in moments of emotional distraction and turmoil. Taking a moment for a few, deep, calming, oxygenating breaths can be useful before, during, and after situations that may be stressful to bring us back to balance.

Practice:

- Sit with your back supported in a comfortable chair and your feet on the floor. Place your hand on your stomach. Close your eyes.

- Breathe in through your nose in four counts, feeling your stomach instead of your chest rise.

- For the next four counts, hold the breath in your lungs, then for the next four counts, exhale through your mouth with pursed lips. Feel your stomach deflate slowly as you exhale.

- As you’ve completely exhaled, count to four before taking an inhale once more.

- Repeat at least three more cycles of this. Notice the sensation of the air going through your nose, through the back of your throat and into your lungs. Notice as well the rising and falling of your hands on your stomach, keeping your attention to the act of breathing.

- Should your mind start to wander, notice it wandering and acknowledge the distraction, gently bringing back your attention to your breath each time.

Throughout the earlier movies (original and prequel trilogy) and media of the Star Wars franchise, The Force was thought to only be an ability that could only be accessed by a few gifted individuals who were taken to train under the Jedi or the Sith. In the newer movies (sequel trilogy), this is re-written. Luke teaches Rey under his tutelage in the sequel trilogy’s The Last Jedi that The Force is not a superpower, it is an energy that she can harness and has no owner; it moves freely within and among the beings of the universe. The Force belongs to every being. It is no longer about genetics (or midi-chlorian count), no longer about intelligence. It is simply anyone’s ability to notice without judgment, exactly like mindfulness. It is simply an ability that can be honed in due time when practiced. Like a muscle trained to lift in increasing incremental amounts, we, too— regardless of background, of stature, of origin— can train our own minds to become more mindful. Luke’s messages are powerful, in the same way that we are empowered knowing our thoughts, feelings, and impulses are simply material that flows within us and do not define us.

And like every Padawan in the quest of seeking mastery of The Force under a Jedi Master; we too, can seek help to empower ourselves in strengthening our capacity for mindfulness, either through reading books or articles, watching videos or documentaries, attending workshops and seminars, and enlisting the help of a trained mental health professional to help us train ourselves to become mindful in daily practice. With commitment to making it a habit like how the Jedi practice meditation daily, and allowing ourselves to acknowledge both our Light and Dark sides, we, too, can harness The Force, the mindfulness to overcome the challenges that we face in our lives while making it meaningful. May The Force be with you!

Sources:

- Feichtinger, C. (2014). Space Buddhism: the adoption of Buddhist motifs in Star Wars. Contemporary Buddhism, 15(1), 28-43.

- Friedberg, R. D., & Rozmid, E. V. (Eds.). (2022). Creative CBT with Youth: Clinical Applications Using Humor, Play, Superheroes, and Improvisation. Springer Nature.

- Fuyu, & Fuyu. (2023, April 11). What is the Eightfold Path? | Zen-Buddhism.net. Zen Buddhism | SIMPLE WISDOM FOR HAPPY LIVING. https://www.zen-buddhism.net/what-is-the-eightfold-path/

- Hayes, S. C., & Hofmann, S. G. (Eds.). (2018). Process-based CBT: The science and core clinical competencies of cognitive behavioral therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

- Linehan, M. M. (2014). DBT Skills Training: manual. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB18848503

- Ratcliffe, A. (2020). The Jedi Mind: Secrets from the Force for Balance and Peace. Chronicle Books.

- The Human Condition. (2021, June 11). An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. https://thehumancondition.com/an-introduction-to-zen-buddhism/