In We Thrive, cultivating “authenticity” is a core component of our work. That said, there is vibrant debate across various disciplines over what exactly it is: for example, is authenticity something that is always there and waiting to be “discovered”, something that “emerges” through our various experiences, or some magnificent combination of both? (Psychology Today, 2023) But as a working definition, we can think of authenticity as a process of making the “whats” and “hows” of life work in tandem with the “whys” of life. Adding some specificity, it is the extent to which we are “consistent” (i.e. ensuring “external characteristics” and “internal values” match); are in “conformity” (i.e. ensuring life’s broad strokes meet whatever standards we set for ourselves); are able to “connect” (i.e. how our relationships to a place, a community, or historical milieu align with our sense of self); and have “continuity” (i.e. how much of our sense of self changes or is retained over time) (Dammann, Friederichs, Lebedinski, and Liesenfeld, 2020). Put more succinctly, authenticity “requires us to embrace the reality of our freedom and be responsible for how we choose to live” (Sutton, 2021). To be able to live a life that is consistent, in conformity, is connected, and has continuity, we must exercise an awareness of life’s movements and, to the extent possible, ensure that these movements work in harmony.

Whenever Pride Month rolls in every June, the idea of “authenticity” inevitably comes up. For LGBTQ people, one marker often used to evaluate whether we are living authentically is disclosure of one’s sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) — that is, “coming out”. Many LGBTQ people see coming out as a cornerstone to the lifelong task of embracing this responsibility over life and maintaining the harmony of life’s hows and whys. And wonderful as it might be, and as important as it is in our collective imaginations, it needs to be said that it is not the end-all and be-all of authenticity as an LGBTQ person. You do not have to be “out” in order to be true to yourself. So the intention here is not to give undue privilege to coming out, but to ask what coming out might contribute to our own journeys of living authentically.

Ultimately, it is on each of us to pay attention to what life is specifically asking from us — to “listen to those messages”, as the therapist Andrea Matthews explains, “listening long enough and deeply enough to really suss out the most essential parts and then begin to act as needed” (Matthews, 2023). Whether coming out is what life demands of us in the present is on us to ascertain, and with much necessary struggle. But thankfully, that difficulty is at least a good sign: as the professor of psychology Dr. Stephen Joseph puts it: “the most authentic people, because they know themselves so well, recognize their struggles in living authentically” (Joseph, 2020).

Even if life does ask this from us, coming out can be deeply frustrating. We may have to come out in bits and pieces: to one friend but not another, with a sibling but not necessarily with a parent, and so on. In these scenarios, LGBTQ people can be caught up in an exhausting balancing act of shifting between one’s “personas” from one context to the next.

We may feel unable to come out at all because of what may be real risks to our wellbeing and safety, whether that be threats of violence or serious disruptions of important relationships such as those in our families or religious communities. We may even struggle with “coming in” — that is, recognizing and accepting oneself as LGBTQ — whether because of internalized negative ideas about being LGBTQ (e.g. “LGBTQ people are promiscuous”), perceived conflicts with core beliefs (e.g. “same-sex relationships are sinful”), and any number of barriers to our ability to embrace our unique experience of SOGI.

Whatever the case, our response to our circumstances must have at least two features: a loving-kindness; and a gentle recognition that these struggles allow us opportunities for renewal that can surprise us in the way it moves us closer to authenticity than our preconceived notions of coming out ever could.

Speaking of renewal, like other aspects of life, our experience of SOGI is always undergoing this process: we learn more about the nature of our attraction to others; who we are as men, women, or some other gender category; and what influences how we respond to relationships. For example, while the rule of thumb is that sexual orientation is generally stable over a lifetime, some very clever research has shown it can also display a good deal of fluidity, such as in studies that looked at differences in its expression based on birth sexes (Mock and Eibach, 2012) or specific timescales (Diamond, Dickenson, and Blair, 2016). This fluidity is also the case for gender identity (Katz-Wise, 2020), and is readily seen both historically and in the present time both in our own culture and in the surrounding cultures of Southeast Asia (Peletz, 2006). Such fluidity is undoubtedly fascinating in and of itself. But more importantly, it raises many points of reflection: for example, how much of our experience of authenticity is invested in our experience of SOGI, given its potential fluidity? (This question certainly applies to many other areas of life!) Applying this question to coming out: how much of the movements of life — our aspirations, beliefs, talents, interests, and capacities for truth in our relationships — is invested in our coming out, given how fluid coming out can also be?

There are many ways we can break this question down further. But as a starting point for what is ultimately a lifelong process, we can briefly apply some practical points of reflection on authenticity offered by the clinical social worker Zahara Williams:

- Does coming out allow you to be “in tune with your values and passions”? For example, is being more open about your SOGI directed towards your personal commitment to the principle of honesty? Or does being more open about your SOGI also translate to being more open to embracing interests and desires which norms surrounding gender and sexuality would otherwise stop you from pursuing?

- Does coming out contribute to a feeling of “being fulfilled?” For example, would being more open about your SOGI open up avenues in your life that allow you and others a fuller experience of who you are and what your life has to offer?

- Does coming out help you “navigate life with purpose?” For example, would greater honesty about your experience of being an LGBTQ person allow you to act with more honesty about what you want out of life?

- Is coming out for you “prioritizing what brings you peace”? For example, would disclosing your SOGI, whether or not this is initially difficult or distressing, ultimately give you the peace of mind you need to move through life with more ease and without so many considerations of people’s responses?

- Does coming out give you more “tenacity and flexibility?” For example, would facing the challenge of coming out as LGBTQ embolden you to face courageously all the other challenges life offers you? (Psych Central, 2022)

To emphasize a previous point, coming out is a “lifelong process”, and our answers to the questions like what gives us a sense of fulfillment or peace are themselves very fluid. You may have also discovered that there were just as many other questions as there were answers which emerged. Perhaps while looking back at your own experience, as I did while writing this article, you realized that there was a time before coming out where the various affections of life came less naturally then than it does now. You may also have noticed that, despite the very real difficulties that entered into life as a result of coming out, there also came very real joys. And perhaps there were things which you would not expect to be at all related to disclosing one’s SOGI — in my case, these were my renewed religious pieties and an enthusiasm for sports — which now have such a profound influence on the movements of your life after coming out.

If these questions seem difficult, that is because they are. But as we see from some of these questions, coming out can be a starting point for a fuller experience of life’s truths. Using the components of authenticity identified earlier on: does coming out allow us to direct the movements of life in ways that allow us to live a life that manifests consistency, conformity, connection, and continuity? Whether or not we choose to come out, what is important is that we are able to exercise that sensitivity to the movements of life so that we are able to be true to ourselves in the present moment.

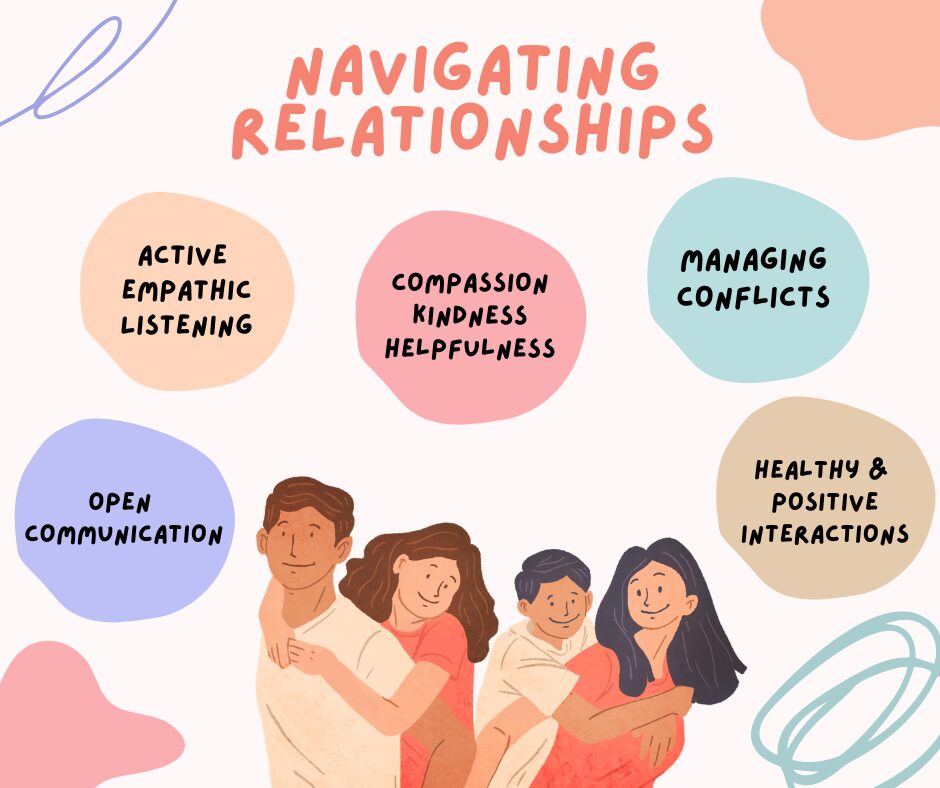

Whatever the case, We Thrive aspires to be your ally. Whether it’s about coming out, navigating your relationships with others, and figuring out how your SOGI fits into other aspects of life in a beautiful way, we want to be with you in your journeys.

To learn more about how our different activities and programs can contribute to your wellbeing as an LGBTQ person, email us at resilientteams@wethrivewellbeing.com.

References:

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/authenticity

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.629654/full

- https://positivepsychology.com/authentic-living/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/traversing-the-inner-terrain/202305/how-to-live-an-authentic-life

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/what-doesnt-kill-us/202007/are-authentic-people-more-mindful

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21584828/

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/gender-fluidity-what-it-means-and-why-support-matters-2020120321544

- https://psych.utah.edu/_resources/documents/people/diamond/Stability%20of%20sexual%20attractions%20across%20different%20timescales.pdf

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/498947

- https://psychcentral.com/lib/ways-of-living-an-authentic-life